Is It CAS? Navigating Differential Diagnosis

Childhood Apraxia of Speech or CAS can be a particularly tricky speech disorder to diagnose.

You assess a highly unintelligible child, and after giving a battery of tests and carefully looking at the results, you still wonder, is it CAS? How can I tell? Just how does CAS look different from a severe phonological disorder? Has this happened to you? I’ve been there, and I knew I needed to learn more.

|

| Childhood Apraxia of Speech can be difficult to diagnosis- so how do you know if it’s CAS? |

This is Part 2 in my series on Childhood Apraxia of Speech, Let’s Talk!

This April, I was selected to be part of a CAS intensive training workshop sponsored by the Once Upon a Time Foundation and the Department of Audiology and Speech-Language Pathology of the University of North Texas. Twenty-five SLPs were invited to spend three days and evenings with Dr. Edythe Strand, of Mayo Clinic, learning from her expertise in the area of CAS.

Read my first post in this series, Childhood Apraxia of Speech: What SLP’s Need to Know to learn more about Dr. Strand and just what childhood apraxia of speech really is.

Please be aware, I’m not an expert in childhood apraxia of speech. I’m learning, just like you. I figure if I have questions and doubts about how to approach CAS, some of you may too. Dr. Strand, who is an extraordinary clinician, researcher, and teacher, shared her experience and expertise with us. I’m sharing what I learned with you, with Dr. Strand’s permission and blessing. So let’s talk about diagnosis.

Differential diagnosis: How do I know if a child has CAS?

Praxis or Planning Deficits Versus Execution Deficits

What is Praxis?

Difficulty planning muscle movements of the articulators for speech is termed childhood apraxia of speech or CAS.

Difficulty planning oral movements not related to speech is termed oral non-verbal apraxia.

What do we mean by “execution deficits”?

1. reduced range of motion

2. reduced strength

3. reduced speed

The only type of dysarthria that is not associated with weakness is ataxia. This can make it difficult to differentiate from apraxia, but the good news is ataxic dysarthria is treated with the same approach as apraxia.

(Wide-based gait may one thing you notice with ataxia.)

Is this getting deep? Breathe, you’ve got this.

OK, We’ve got our labels. That’s not so bad now is it? But here’s the rub: Children do not fit neatly in just one box. So you may see a child with two or even all three of these labels. These deficits can co-occur. A child often has apraxia and phonological impairment as well. Or maybe apraxia plus weakness.

Our labels can change over time as a child progresses and develops.

Children change. Characteristics of a disorder look different with time and therapy. Labels should change with them. You may have a new student or client that comes with a history of CAS. Yet, that label may or may not be currently appropriate.

You’ll want to review your labels and do a differential diagnosis as children progress to see if they are still appropriate.

If the labels can change, how do they help? Labels help us guide our current treatment approach. For instance, a child who may have presented with characteristics of CAS initially may present with residual phonological impairment more than apraxia as time goes on. Treatment approaches can, therefore, change as well.

|

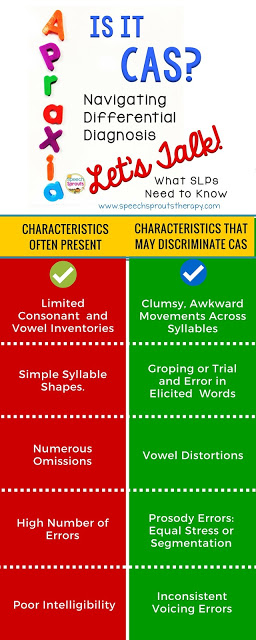

| Some characteristics are more likely to discriminate CAS than others. Learn what to look for! |

Now for the nitty-gritty. What characteristics are present in CAS?

Characteristics that may be present, but are not exclusive to CAS:

- Numerous errors and poor intelligibility may be seen in children with all types of speech sound disorders (SSD’s), whether the child has dysarthria, CAS or a phonological impairment.

- Substitution errors may occur more in children with phonological impairments.

Characteristics that are more likely to discriminate CAS:

1. Difficulty moving from one articulatory configuration to another. You may see awkward or imprecise movement as the child tries to move smoothly across the syllable. (For instance when attempting to say peek-a-boo). Errors may increase with the number of syllables in a word and complexity.

2. Groping or trial and error on initial consonants. You will usually see this more in elicited words but not in spontaneous speech.

3. Vowel Distortions. This is not a substitution of the vowel, rather the intended vowel is distorted.

4. Errors in Prosody. Lexical stress pattern errors: you may see equal, even stress or pauses between phonemes or syllables causing segmentation. (ex. instead of banana, you get ba-na-a)

5. Inconsistent Voicing Errors. It may be hard to tell if the consonant is voiced or unvoiced, due to errors in the timing of voicing onset.

These characteristics are more likely to be seen in children with CAS, and less likely to be seen in children with other speech sound disorders (SSDs).

|

| It’s important to differentiate CAS from other speech disorders! Learn more by following this series on childhood apraxia of speech. |

Whew! That’s a lot of information.

Are you hanging in there? So far, we talked about the definition of CAS in my first post Childhood Apraxia of Speech: What SLP’s Need to Know. Today, we covered key terms you need to know and characteristics you may see in CAS.

Questions? Thoughts? I would love to know what has been helpful for you. Any aha moments yet? Anything you would like to know more about? I encourage you to leave me a comment, let’s talk! Please remember, I am not an expert, but I will try to answer or find a resource for you.

For more information, you may want to head over to ASHA’s Practice Portal on CAS.

Dr. Strand has a YouTube series you need to check out.

Thanks for reading!

If you are finding these posts helpful, please follow and share. Pin, post, and help spread the word. Increasing our knowledge base is so important for children with childhood apraxia of speech!

4 Essential Steps in Assessing Childhood Apraxia of SpeechUntil next time!

Share it:

- Read more about: Articulation