How to Create an Amazing Therapy Plan for Childhood Apraxia of Speech

This is Part 5 of my series for SLPs on Childhood Apraxia of Speech: Let’s Talk!

Today, we are going to talk about planning your therapy for CAS.

Congratulation my friends. If you’ve arrived here after reading my childhood apraxia of speech series, we’ve made it through a lot of assessment information together. I’ve been sharing what I learned from a top expert in the field and an absolutely wonderful clinician, Dr. Edythe Strand of the Mayo Clinic.

I hope you have a better understanding of how to plan an evaluation for a child whom you suspect has childhood apraxia of speech and how to make your differential diagnosis. I really think that’s the hard part! We even learned how to identify emerging skills that will be great starting points in therapy. So now, it’s time to get a therapy plan going and get some progress rolling for your student.

If you’re just joining in, I recommend reading the earlier posts and then catching up with us here. You can find the first post in this series here: Childhood Apraxia of Speech: What SLPs Need to Know. It’s okay, Go ahead. I’ll wait!

So let’s talk about the principles of motor learning theory and making progress with childhood apraxia of speech.

This is important to your therapy plan, I promise. Let’s think about this. We want to improve skills in motor planning, retrieval, and carrying out the muscle movements (motor movements) needed for speech. So we need to know what research says is the most efficient way to do that.

Motor learning theory has been applied to the rehabilitation of limb movements for many years, and in the last 15-20 years, to the treatment of CAS.

Some studies have supported its application to speech movements, others have not. Speech is, after all, a complex behavior, involving language and motor movements. The severity of childhood apraxia of speech appears to be a large factor.

So what needs to happen to learn a motor skill? We need practice. Lots and lots of repetitive practice of the movement. How did you learn to ride a bike? Steer a car? Did you do this smoothly at first? Probably not, but the more practice you got, the better you were. You practiced until the movements came automatically.

First things first.

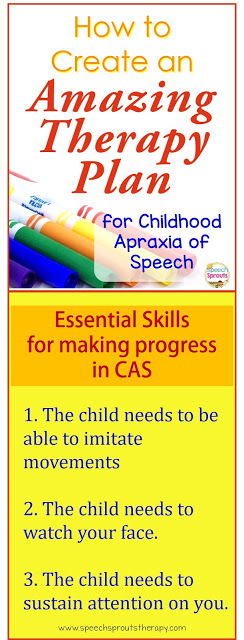

We need a few skills in place to make the most progress. The child needs to be able to imitate you, be willing to watch your face and maintain attention. If these aren’t in place yet, build these into your therapy plan.

Here’s how:

1. The child needs to imitate your movements. Do a few minutes of warm-up, where you practice imitation of your movements. Reinforce imitation of large movements- arms waving, clapping, then finer movements, fingers wiggling, then oral movements: moving your jaw, lips, and tongue. Talk about and practice the difference between big movements and little movements, fast movements and slow movements. Draw attention to how the movement feels. Does it feel tight? Now let’s try it loose.

1. The child needs to imitate your movements. Do a few minutes of warm-up, where you practice imitation of your movements. Reinforce imitation of large movements- arms waving, clapping, then finer movements, fingers wiggling, then oral movements: moving your jaw, lips, and tongue. Talk about and practice the difference between big movements and little movements, fast movements and slow movements. Draw attention to how the movement feels. Does it feel tight? Now let’s try it loose.

2. The child needs to watch your face: Hold activities and reinforcers near your face, not on the table. Desirable items on the table will encourage the child to look away from your face, we don’t want that. Be sure to place the child at eye level with you. Raise the child, or lower yourself! Dr. Strand sometimes puts them on top of her desk. I tried that, and it works great. Face to face, with no table in between. Attention is on your face.

3. The child needs to able to sustain attention on you. Use activities that are motivating, but really quick. Don’t let motivational activities distract the child’s focus. Get back to practice immediately. The more responses per session, the faster the progress!

Now, let’s talk about what motor learning theory says about scheduling practice.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

How often should therapy sessions be scheduled? How many words should I work on in a session?

* Mass practice may be scheduling 5 sessions in one day or one really long session a week. It can also mean working on a very small set of words per session. You get a ton of practice in a short period of time. Mass practice will lead to the quick development of a skill. However, carryover and generalization to other motor movements and words is poor. So this might be the initial option for severe, highly unintelligible children to help them be more accurate with a small core vocabulary they can use and get them communicating verbally. Work on only 5-7 words per session, and schedule many frequent sessions. Later, you will want to move to distributed practice.

* Distributed practice may be working on 10 different words in a set during a session, or scheduling less frequent sessions. Distributed practice yields slower progress, but better learning and generalization.

* Block Practice is practicing each word in a block of many repetitions. For instance, practice “me” 50 times, then “mine” 50 times, then “up” 50 times. You’ll get better performance on trained words, but less generalization. A “modified” block may look like 50 repetitions on “me”, 50 reps on “mine” and 20 reps on “up”.

* Random Practice is taking those same words and mixing them up randomly. Say “mine” then “me” then “up”. This yields better motor learning, but slow progress.

Vary your set of practice words and how they are presented.

Movement sequences should be practiced under different conditions and contexts to improve motor learning. Choose a movement sequence, but practiced varied examples, different coarticulatory contexts and manners of production. For instance, you could choose a bilabial to a vowel. Your set could include me, my, bee, baby.

Don’t forget prosody!

Work on this early and often. Once the child is successful in one context, practice the word or phrase loud and soft, high and low, normal or slow. Say it as a statement or with rising question inflection. Go out! Go out! Go out? Just be sure you never segment your model. Teach “shhhhhhhoooo” and not “sh”+”oo”.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

What should feedback look like?

* Intrinsic feedback is sensory information- what the child hears or sees or feels. Sensory feedback may not be enough in CAS.

* Extrinsic feedback, which provides information on how accurate the attempt was “That’s right!” and what the child needs to do differently “Be sure your lips are together.” This is especially important early in treatment. As a child progress, reduce extrinsic feedback, so the child doesn’t become overly dependent on feedback and can improve self-monitoring.

The amount of feedback needed changes over time. Start with frequent, immediate feedback, and move towards intermittent feedback with greater delays in delivery.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

So what do you do exactly?

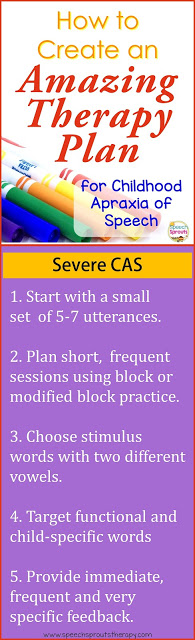

For the child with severe childhood apraxia of speech, start with mass practice and blocked practice, with frequent and immediate feedback.

1. Start off with a small stimulus set of 5-7 utterances.

1. Start off with a small stimulus set of 5-7 utterances.

2. Plan shorter, more frequent sessions using block or modified block practice.

3. You may want to choose stimulus words with two different vowels.

4. Target functional words such as hi, bye, out, ow, or down. Check with family to see what words are important to the child: a pet’s name, favorite toy, family names, and his own name are all good targets to include for functional speech.

5. Provide immediate, frequent, and very specific feedback.

As the child progresses, move toward distributed practice and random practice, with less frequent feedback, delivered with greater delays.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

You’ve done it! You have an awesome therapy plan in place for your student.

We have our diagnosis, we’ve identified emerging skills and functional words to target, and we’ve designed a therapy plan with careful consideration of the intensity and frequency of practice and feedback. As our preschool teacher would say… “Kiss your brain!”

NOTE: Next time I will be talking about Dynamic Temporal and Tactile Cueing (DTTC) and some awesome therapy techniques, tips, and tricks, so stay tuned, my friends.

See you soon, and please don’t forget to share this post so we can spread the word!

Share it:

- Read more about: Apraxia, Articulation